Pregnancy blog, like the Researchers’ Network, aims to reach beyond boundaries and borders, and to facilitate an international and interdisciplinary conversation on pregnancy and its associated bodily and emotional experiences from the earliest times to the present day. This week Kate Cornforth considers Naomi Campbell’s recent birth announcement.

‘How DID Naomi Campbell welcome a daughter at 50?’[1]

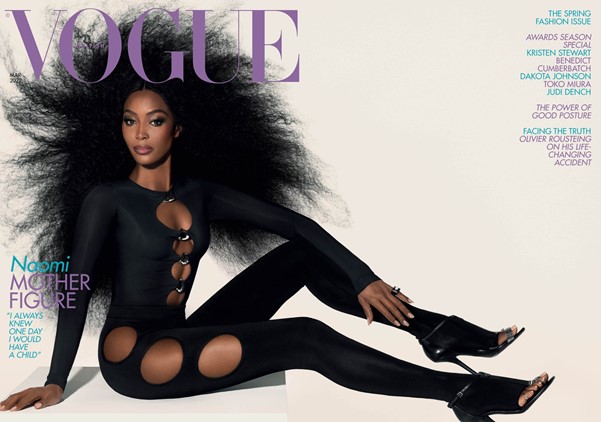

“I can count on one hand the number of people who knew that I was having her,”[2] Naomi Campbell has appeared this week on the front cover of VOGUE with the title of her exclusive interview, ‘Motherhood On Her Own Terms’, and I, like thousands of others, immediately wondered: How has she done it? Can people have babies in their 50s?

Then I challenged myself.

As a scholar researching the representation of the pregnant body, I am fanatical about questioning why pregnant bodies remain confined to ideologies under the eye of public scrutiny. I argue that there is a ‘dominant pregnancy script’, seen in fiction, film and on social media that impacts on, and restricts, how one is not born, but rather becomes, a mother.[3] Naomi Campbell has become a mother, and people are concerned about ‘how?’ because she has not conformed to the dominant pregnancy script, or patriarchal ideal of pregnancy and parenthood that means that to ‘do’ pregnancy correctly is to be heterosexual, able-bodied, financially stable, and, unlike Naomi Campbell, the ‘correct’ age.

Breaking down the dominant pregnancy script

Naomi Campbell has broken the dominant pregnancy script and followed ‘her own’ feminist pregnancy script.[4] The focus of my research, the Feminist Pregnancy Script (FPS), challenges the ‘dominant pregnancy script’ of the past and encourages choice throughout pregnancy. Campbell’s approach to her own pregnancy epitomises the FPS: Vogue highlights how she continues to be ‘a force for change and to demand greater Black representation in an industry long criticised for its lack of diversity’. The FPS is just such a ‘force for change’, challenging people’s perceptions of pregnancy, ultimately underlining that there is no ‘correct’ way to do pregnancy.

More than that, though, the FPS is not only for pregnant people. It emphasises the importance of the behaviour and attitudes of non-pregnant people. For change to happen, there must be a cultural shift in others’ attitudes toward the pregnant body: judgemental discourse around pregnancy can be dismantled by celebrating diverse, feminist pregnancies.

No but really, how did she do it?

‘Pregnant bodies are public bodies, so pregnant women are also regulated by others – health-care professionals, family members, friends, and even strangers.’[5]

First the pregnant body is under constant scrutiny; then how one chooses to mother or parent is up for examination shortly after. The newspaper articles say it all: ‘She wasn’t adopted – she’s my child’ and ‘Naomi Campbell confirms baby daughter is not adopted’. The Daily Mail’s ‘Femail’ section has been quick to ‘reveal how she could have cleverly hidden a bump after fertility treatment or used a surrogate to carry her child’.[6]

Instead of wondering ‘how?’ we should ask ‘why do we care?’. Naomi Campbell is on the front cover of a major magazine; a Black mother who has not conformed to the dominant pregnancy script. Let’s reach the point where we all follow the Feminist Pregnancy Script, where we congratulate rather than challenge, celebrate rather than scrutinise.

Be more feminist.

Kate is a PhD student from the Institute of Gender Studies at the University of Chester, U.K. Her thesis, Following a Feminist Pregnancy Script: The Representation of the Pregnant Body in Contemporary Fiction, Film and on Social Media focuses on the struggles that pregnant people face during the gestation and postpartum period, particularly when the pregnancies are ‘unborn’, ‘unheard’ or ‘unsaid’. With her past work including The Representation of Pregnancy and Childbirth in the Nineteenth-Century British Novel, she is keen to research the literature, film and social media of today to understand what it is like to be pregnant in 2022, and to conceptualise a new theory called the ‘feminist pregnancy script’, an inclusive guide for all types of pregnancy.

[1] Stephanie Linning, How DID Naomi Campbell welcome a daughter at 50? (2022) <https://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-10514323/How-DID-Naomi-Campbell-welcome-daughter-50.html> [accessed 15 February 2022]

[2] Sarah Harris, A Model Parent: Naomi Campbell Opens Up About Motherhood On Her Own Terms (2022) <https://www.vogue.co.uk/fashion/article/naomi-campbell-british-vogue-interview> [accessed 15 February 2022]

[3] A re-visioning of Simone de Beauvoir’s famous: ‘one is not born, but rather becomes, a woman’.

[4] Harris, A Model Parent: Naomi Campbell Opens Up About Motherhood On Her Own Terms

[5] Elena Neiterman, and Bonnie Fox, ‘Controlling the unruly maternal body: Losing and gaining control over the body during pregnancy and the postpartum period’, Social Science and Medicine, 174, (2016), 142-148, <https://www-sciencedirect-com> [accessed 4 March 2019], p. 145.

[6] Linning, How DID Naomi Campbell welcome a daughter at 50?