Pregnancy blog, like the Researchers’ Network, aims to reach beyond boundaries and borders, and to facilitate an international and interdisciplinary conversation on pregnancy and its associated bodily and emotional experiences from the earliest times to the present day. This week Julia Gruman Martins introduces a new Being Human event that encourages us to think about the connections between the history of birth and modern practices.

In a quick Internet search, pregnant people are faced with a wealth of information about how to make childbirth easier: dimmed lights, a warm environment, the use of soothing smells such as lavender, relaxing massages, affirmation words, breathing techniques, how to stay nourished, and calming sounds are often mentioned. In addition, people are told how movement and different positions can facilitate the delivery and how birth partners may help. From the NHS website to the many experts who offer their services, be they midwives or doulas, these are recurring aspects of how to make childbirth better and safer: an easier, happier, and ultimately more empowering experience to the one giving birth.

Yet many of these elements are frequently met with resistance by several in the medical establishment and other institutional settings, criticised as ‘new-age’, feminist-inspired, ‘hippie’ trends. Moreover, many of the arguments against these practices (even though most of them are evidence-based) give us the impression that the campaign for a change in how people give birth proposes a radical break with how babies were traditionally born, a rupture with the status quo.

However, as medical historians have shown, the many male-dominated, sterile, ultra-lit delivery rooms of hospitals of the present are new in the history of childbirth.

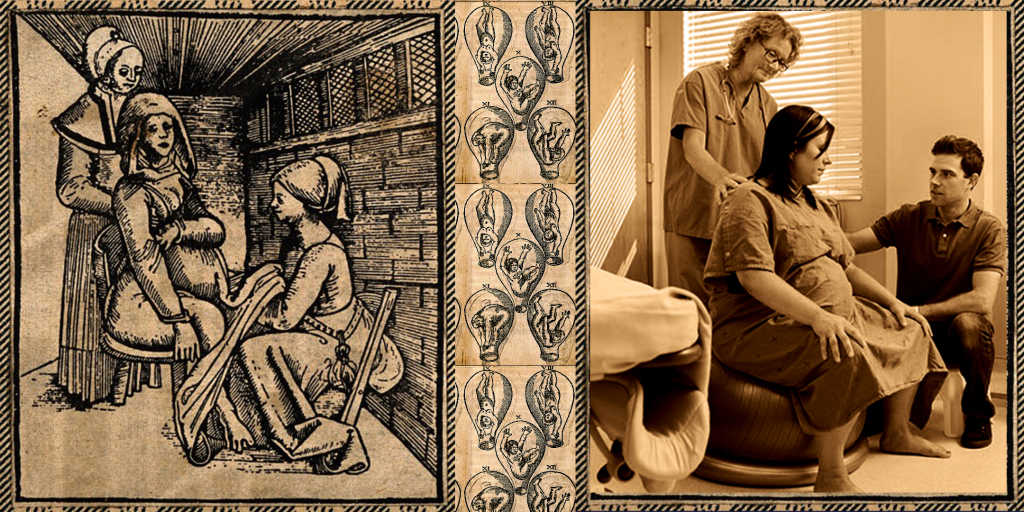

Going back to the early modern period, a delivery room would be warm, dimly lit, and perfumed with medical herbs. The birthing woman would probably be attended by a midwife and surrounded by female friends and relatives – her ‘gossips’. She would be offered sustenance in broths and fortified wine and would be advised on different positions depending on her body type and the way the baby was positioned. Skilled midwives could even manipulate the baby in the womb to facilitate the birth.

Yet this is not how most people imagine babies being born during the time of the Tudors – in large part thanks to the sensationalised way childbirth is represented in period films and TV series. These media make pregnant people glad to be giving birth in the 21st century, thinking of this barbaric past as something alien to them.

However, there is much that we can learn about how to make childbirth better today from the way women gave birth in the past. It is not a matter of comparing what was ‘better’ or ‘worse’ then (although a strong case could be made regarding pain relief options for birthing people today!). We should resist the temptation to see the past as ‘other’ in the same way we should avoid idealising it.

There are many continuities in the history of midwifery and childbirth, even though the way we perceive the body has changed (such as our current understanding of hormones and their role in birth). For instance, a seventeenth-century midwifery manual advised that ‘you must lay the woman in a dark place, lest her mind should be

distracted with too much light’.1 The room should also be kept warm since the delivering woman ‘must be kept from the cold air…and therefore the doors and windows of her chamber in any wise are to be kept close shut’.2 Today, birthing people are told that turning off overhead lights and using candles can help the room feel less clinical, keeping it warm and snug and helping the ‘love hormone’ oxytocin flow, facilitating birth. The reasoning behind this recommendation might have changed, but people are still advised to create a womb-like environment to give birth.

Therefore, by studying the history of childbirth, we can understand how we got to where we are today. But we can also add nuance to our debates. We can find continuities in the way people give birth throughout history – not just ruptures. It is possible to learn from how early modern people gave birth and what aspects we can adapt to childbirth today. Therefore, rethinking childbirth considering history can be very helpful in our fight for better and safer practices today.

Interdisciplinarity is critical in this process, yet as medical historians, we can often become disconnected from the realities of giving birth today – even those of us who are mothers! To make childbirth better for all of us, we need to broaden the conversation, including midwives, doulas, pregnant people, historians, physicians, massage therapists, and birth partners.

This November, join us in rethinking childbirth, comparing how people gave birth 500 years ago and today. We will discuss the sharp contrasts between the early modern and the 21st century delivery rooms and the surprising continuities between them, from the lighting to the role of birth partners. It will be an informal conversation between a historian and a practising doula, followed by a Q&A with the audience. Available to book on Eventbrite via the link below.